In this note I will repeat some stuff that I was already explaining in the past, but we will also find some important new stuff.

The time evolution differential equation for the attitude matrix ![]() is

is

(1) ![]()

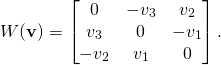

where ![]() is the angular velocity vector in the body frame, and

is the angular velocity vector in the body frame, and ![]() maps any vector

maps any vector ![]() into skew-symmetric matrix as follows:

into skew-symmetric matrix as follows:

(2)

It has the property that for any vector ![]() we have

we have

(3) ![]()

Equation (1) follows immediately from the definition of the angular velocity. The angular velocity ![]() in the laboratory frame is defined by

in the laboratory frame is defined by

(4) ![]()

But ![]() maps coordinates of vectors in the body frame into their coordinates in the laboratory frame. Thus

maps coordinates of vectors in the body frame into their coordinates in the laboratory frame. Thus ![]() and therefore

and therefore

(5) ![]()

But from Eq. (3) we have ![]() therefore

therefore

![]()

and so Eq. (1) follows.

While description of rotations in terms of orthogonal ![]() matrices in principle suffices in classical mechanics, sometimes it is convenient to use the group of quaternions of unit norm, the group isomorphic to the group

matrices in principle suffices in classical mechanics, sometimes it is convenient to use the group of quaternions of unit norm, the group isomorphic to the group ![]() used in quantum mechanical description of half-integer spin particles. Quaternions have some advantages in numerical procedures (as for instance in 3D computer games), but they are also convenient for graphical representation of the intrinsic geometry of the rotation group. And this is what interests us, when we plot trajectories representing history of a spinning rigid body.

used in quantum mechanical description of half-integer spin particles. Quaternions have some advantages in numerical procedures (as for instance in 3D computer games), but they are also convenient for graphical representation of the intrinsic geometry of the rotation group. And this is what interests us, when we plot trajectories representing history of a spinning rigid body.

Quaternions of unit norm, representing rotations, form a 3-dimensional sphere in 4-dimensional Euclidean space, and we are projecting stereographically this sphere onto our familiar three-dimensional space, where we orient ourselves in a usual way known from everyday experience.

The question therefore arises: how the equation describing the time evolution looks like when represented in the quaternion setting?

To derive it we have to return to the fundamental relation between quaternions and rotations of vectors in space.

For every vector ![]() with components

with components ![]() denote by

denote by ![]() the pure imaginary quaternion defined as:

the pure imaginary quaternion defined as:

(6) ![]()

Then to unit quaternion ![]() that is such that

that is such that ![]() there corresponds rotation matrix

there corresponds rotation matrix ![]() such that for all

such that for all ![]() the following identity holds

the following identity holds

(7) ![]()

The second interesting property of the hat map is that for all ![]() we have

we have

(8) ![]()

where ![]() is the commutator. The property follows directly form the definitions and from the quaternion multiplication rules. Every pure imaginary quaternion is of the form

is the commutator. The property follows directly form the definitions and from the quaternion multiplication rules. Every pure imaginary quaternion is of the form ![]() for some

for some ![]()

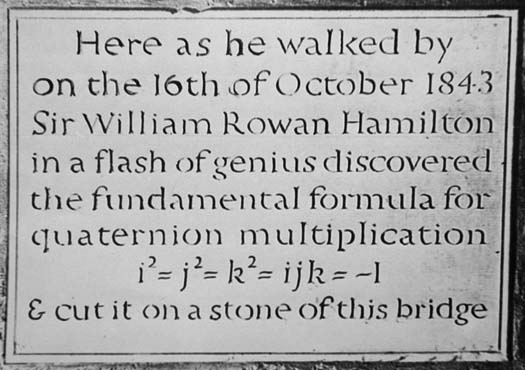

As shown on plaque by the Royal Canal at Broome Bridge in Dublin,

the essence of the quaternions is contained in the four equations

(9) ![]()

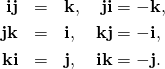

From these, multiplying from the left and/or from the right by ![]() or

or ![]() or

or ![]() we derive

we derive

(10)

From the definition of the hat map we have

(11) ![]()

Therefore

![]()

![]()

When we expand the parenthesis and use the multiplication rules in Eqs. (9),(10), we find that the terms with squares cancel out, while the terms with products like ![]() etc. can be organized as follows

etc. can be organized as follows

![]()

The coefficients in the parentheses on the right are now exactly the components of the cross product ![]()

Thus

![]()

Suppose now that ![]() is a trajectory in the space of unit quaternions, while

is a trajectory in the space of unit quaternions, while ![]() is the corresponding trajectory in the rotation group. Thus we have

is the corresponding trajectory in the rotation group. Thus we have

(12) ![]()

for all ![]() and all

and all ![]() We now differentiate both sides with respect to

We now differentiate both sides with respect to ![]() On the left we use the standard product rule for differentiation, but we pay attention so as to preserve the order, because multiplication of quaternions is non commutative. On the right we enter with the differentiation under the “hat”, because it is a linear operation. We obtain:

On the left we use the standard product rule for differentiation, but we pay attention so as to preserve the order, because multiplication of quaternions is non commutative. On the right we enter with the differentiation under the “hat”, because it is a linear operation. We obtain:

(13) ![]()

Assume now that ![]() is a solution of Eq. (1), so that

is a solution of Eq. (1), so that ![]() We have

We have

(14) ![]()

We now use Eq. (12) on the right to obtain

(15) ![]()

In order to get rid of ![]() we differentiate the defining equation of unit quaternions

we differentiate the defining equation of unit quaternions ![]() to obtain

to obtain

(16) ![]()

or

(17) ![]()

Putting this into Eq. (15) and multiplying both sides on the right by ![]() we obtain

we obtain

(18) ![]()

Multiplying from the left by ![]() :

:

(19) ![]()

From Eq. (16) it follows that the quaternion ![]() is pure imaginary:

is pure imaginary: ![]() Therefore there exists vector

Therefore there exists vector ![]() such that

such that

(20) ![]()

Eq. (19) can now be written as

(21) ![]()

where on the right we have used Eq. (3). Applying Eq. (8) to the left we end with

(22) ![]()

Since the above holds for any ![]() we deduce that

we deduce that

(23) ![]()

Using (20) we finally obtain:

(24) ![]()

Note: It may be that the final formula can be derived in a shorter way, but I do not know how. It is this last formula that I was using when verifying that the algorithm provided in Meeting with remarkable circles gives indeed a solution of the evolution equation.