When we travel by a car, we decide which path to take. Choosing the right path may be crucial. Sometimes we choose a path that is straight, but nevertheless is scary. Like this road in Nebraska:

Sometimes the path is just “unusual”:

And sometimes we will think twice before choosing it:

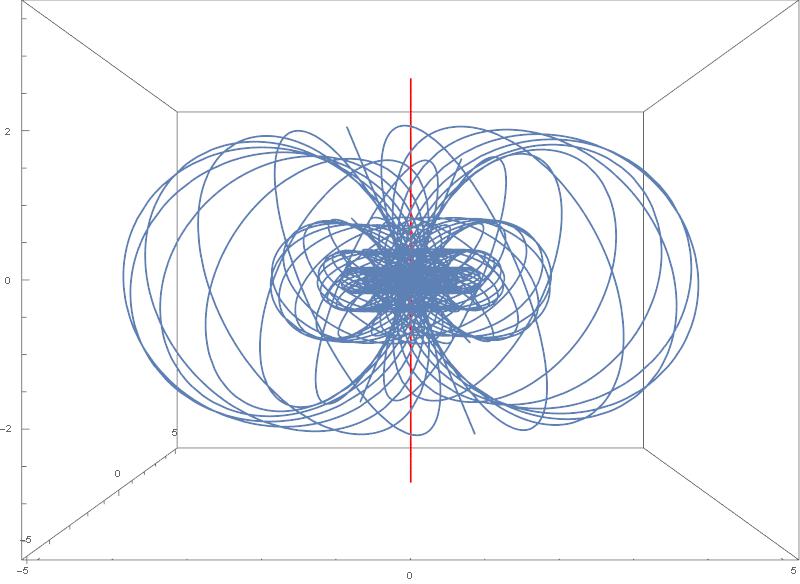

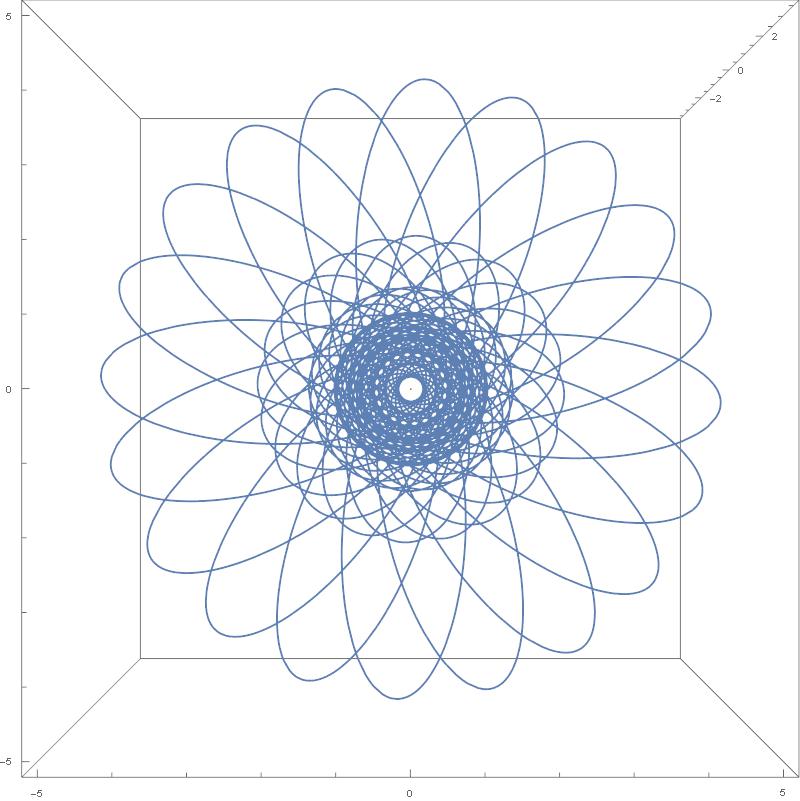

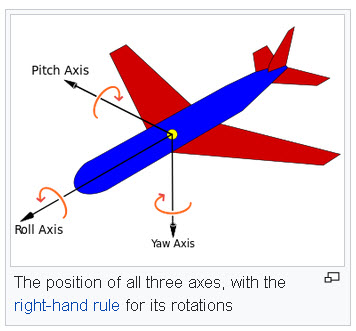

We are interested in a particular kind of traveling: we want to travel in the rotation group. Think of an airplane. When it flies, it of course moves from a location to a location. But that is not what is of interest for us now. During the flight the plane turns and tilts, and all its turns and tilts can be (and often are) recorded. There are essentially three parameters that need to be recorded:

Usually they are referred to as roll, pitch and yaw. When you throw a stone in the air, and if you endow it with three axes, its roll, pitch, and yaw will also change with time. As there are three parameters, they can be represented by a point moving in a three-dimensional space. Instead of roll, pitch and yaw we could choose Euler angles. But, in fact, we will choose still another way of representing a history of tilts and turns of a rigid object as a path. We will use stereographic projection from the 3-dimensional sphere to the 3-dimensional Euclidean space.

You may ask: why to do it? What is the point? What can we learn from it? And my answer is: for fun.

One can also ask: what is the point with inspecting your hand? And yet there is the whole art of chiromancy, or palmistry. From Wikipedia:

Chiromancy consists of the practice of evaluating a person’s character or future life by “reading” the palm of that person’s hand. Various “lines” (“heart line”, “life line”, etc.) and “mounts” (or bumps) (chirognomy) purportedly suggest interpretations by their relative sizes, qualities, and intersections. In some traditions, readers also examine characteristics of the fingers, fingernails, fingerprints, and palmar skin patterns (dermatoglyphics), skin texture and color, shape of the palm, and flexibility of the hand.

We are going to learn about the lines in the rotation group. Some will be short, some will be long. We will learn how read from them about the body that recorded these lines during its flight.

From the internet we can learn:

Which Hand to Read

Before reading your palm, you should choose the right hand to read. There are different schools of thought on this matter. Some people think the right for female and left for male. As a matter of fact, both of your hands play great importance in hand reading. But one is dominant and the other is passive. The left hand usually represents what you were born with physically and materially and the right hand represents what you become after grown up. So, the right hand is dominant in palm reading and the left for supplement.

The same is with rotation groups. Which one to choose? We have rotations represented naturally as ![]() orthogonal matrices, but we can also represent rotations by quaternions or by unitary matrices from the group

orthogonal matrices, but we can also represent rotations by quaternions or by unitary matrices from the group ![]() Both play a great importance. We will choose unit quaternions or, equivalently,

Both play a great importance. We will choose unit quaternions or, equivalently, ![]() they seem to be primary!

they seem to be primary!

Let us recall from Putting a spin on mistakes that every ![]() unitary matrix

unitary matrix ![]() of determinant one is necessarily of the form

of determinant one is necessarily of the form

(1) ![]()

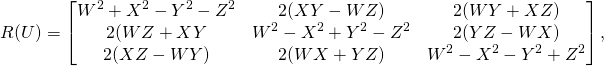

and it determines the rotation matrix ![]()

(2)

where ![]() are real numbers representing a point on the three-dimensional unit sphere

are real numbers representing a point on the three-dimensional unit sphere ![]() in the 4-dimenional Euclidean space

in the 4-dimenional Euclidean space ![]() that is

that is

(3) ![]()

The three-sphere ![]() is “homogeneous”, the same as the well-known two-sphere, like a table tennis ball.

is “homogeneous”, the same as the well-known two-sphere, like a table tennis ball.

And yet I want to paint one particular point on our three-sphere, namely the point represented by numbers ![]() It follows from Eq. (2) that the rotation matrix corresponding to this particular point is the identity matrix:

It follows from Eq. (2) that the rotation matrix corresponding to this particular point is the identity matrix:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[I=\begin{bmatrix}1&0&0\\0&1&0\\0&0&1\end{bmatrix}.\]](http://arkadiusz-jadczyk.eu/blog/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-453acb12b4fd3acd05ad232ad4fd3158_l3.png)

I am not going to hide the fact that also the opposite point, ![]() on our 3D ball also produces the identity rotation matrix, that is, in ordinary language: no rotation at all.

on our 3D ball also produces the identity rotation matrix, that is, in ordinary language: no rotation at all.

We are going now to go back to the stereographic projection that has been introduced already in Dzhanibekov effect – Part 2.

The idea is as in the picture below:

except that our sphere is 3-dimensional, and our plane onto which we are projecting is also 3-dimensional. Our North Pole is now the point ![]() our South Pole the point

our South Pole the point ![]() and our “equator”, that is the set of all points on

and our “equator”, that is the set of all points on ![]() for which

for which ![]() is now a 2-sphere rather than a circle like on the picture above. The projection formulas read (see Dzhanibekov effect – Part 2):

is now a 2-sphere rather than a circle like on the picture above. The projection formulas read (see Dzhanibekov effect – Part 2):

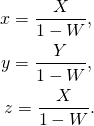

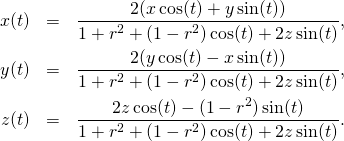

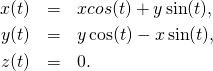

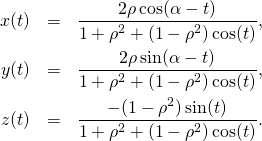

(4)

The inverse transformation is given by

(5)

where ![]()

All the southern hemisphere (points on ![]() with

with ![]() are projected inside the unit ball in

are projected inside the unit ball in ![]() ! The “equator”, where the three-sphere intersects the three-plane, is projected onto the unit sphere in

! The “equator”, where the three-sphere intersects the three-plane, is projected onto the unit sphere in ![]() The North Pole has no image, it is the only point on

The North Pole has no image, it is the only point on ![]() that has no image. In fact, it has an image, but at “infinity”. We will not need it. The South Pole, which, as we know, represents the trivial rotation, is mapped into the origin of

that has no image. In fact, it has an image, but at “infinity”. We will not need it. The South Pole, which, as we know, represents the trivial rotation, is mapped into the origin of ![]() , the point with

, the point with ![]()

We will continue this course of rotational palmistry in the next posts.

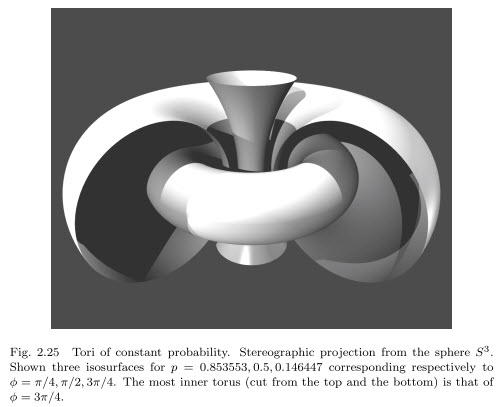

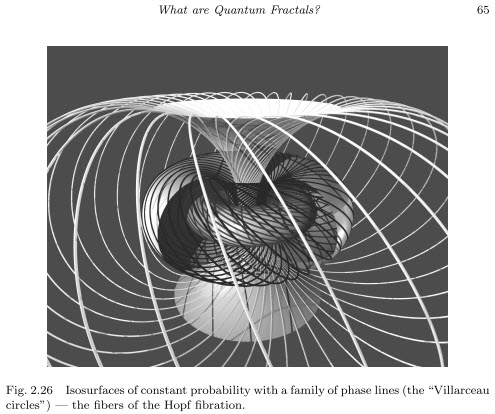

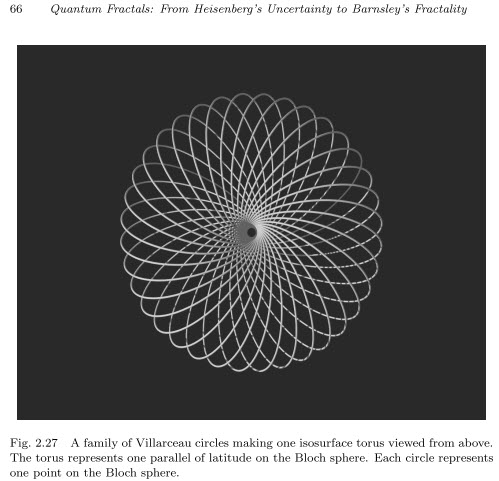

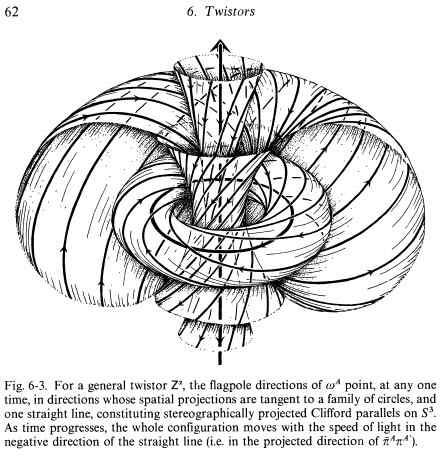

you can find the following images from quantum theory of pure spin 1/2. These images represent what mathematicians often call ‘Villarceau circles’ and ‘Hopf fibration’.

you can find the following images from quantum theory of pure spin 1/2. These images represent what mathematicians often call ‘Villarceau circles’ and ‘Hopf fibration’.