In the last post, SU(1,1) parametrization, we have concluded that the group SU(1,1) has the shape of a doughnut. Its elements can be uniquely parametrized by an angle ![]() and a complex number

and a complex number ![]() inside of the unit disk:

inside of the unit disk: ![]()

Thus SU(1,1) can be parametrized using the Cartesian product of the circle and the (interior of) the disk. But parametrization is one thing, and the actual construction is a different thing. Today we will see how every SU(1,1) matrix can be uniquely decomposed into a product of disk parametrized positive part, and circle parametrized unitary part.

We already know that every SU(1,1) matrix ![]() is of the form

is of the form

(1) ![]()

with

(2) ![]()

We also know (see Eqs. (11,14,15) from SU(1,1) parametrization) that it determines ![]() and

and ![]() so that

so that

(3) ![]()

(4) ![]()

(5) ![]()

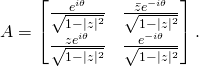

Thus, writing it explicitly, ![]() is of the form:

is of the form:

(6)

But then, as you can easily check, ![]() can be written as a product (so called polar decomposition)

can be written as a product (so called polar decomposition)

(7) ![]()

where

(8)

(9) ![]()

with ![]() and

and ![]()

The matrix ![]() is evidently Hermitian:

is evidently Hermitian: ![]() It is also positive. Hermitian matrix is positive when all its eigenvalues are positive. In two dimensions there are two eigenvalues. Their product is the determinant, and so it is equal to 1. Thus either both eigenvalues are positive or both are negative. But the trace of

It is also positive. Hermitian matrix is positive when all its eigenvalues are positive. In two dimensions there are two eigenvalues. Their product is the determinant, and so it is equal to 1. Thus either both eigenvalues are positive or both are negative. But the trace of ![]() , which is the sum of eigenvalues, is positive

, which is the sum of eigenvalues, is positive ![]() is positive, therefore both eigenvalues must be positive, and so

is positive, therefore both eigenvalues must be positive, and so ![]() is positive.

is positive.

Exercise: calculate the two eigenvalues of ![]()

In fact every positive matrix from SU(1,1) is of the form ![]() for some

for some ![]() Since suppose

Since suppose ![]() is in SU(1,1) and is positive. We write it in the form as in Eq. (6). Positive matrix must be Hermitian, therefore

is in SU(1,1) and is positive. We write it in the form as in Eq. (6). Positive matrix must be Hermitian, therefore ![]() must be real. This happens only for

must be real. This happens only for ![]() or

or ![]() But

But ![]() so for

so for ![]() we would have

we would have ![]() which is impossible for a positive matrix. Therefore

which is impossible for a positive matrix. Therefore ![]() and

and ![]()

The matrix ![]() is evidently unitary,

is evidently unitary, ![]() In fact, every unitary matrix from SU(1,1) must be of the type

In fact, every unitary matrix from SU(1,1) must be of the type ![]() Why? Suppose

Why? Suppose ![]() in SU(1,1) is unitary. Write it in the form

in SU(1,1) is unitary. Write it in the form ![]() Suppose

Suppose ![]() Then

Then ![]() But

But ![]() is unitary and

is unitary and ![]() is Hermitian, so

is Hermitian, so ![]() Thus squares of the eigenvalues of

Thus squares of the eigenvalues of ![]() are both equal to

are both equal to ![]() and since

and since ![]() is positive, both must be equal to 1. Therefore

is positive, both must be equal to 1. Therefore ![]() and so

and so ![]()

Now, being familiar with the polar decomposition, we can fly, like these polar birds

and we will.

(6) is bad.

(8) is transposed?

Thanks. (6) fixed. I do not see problems with (8).

(12) is a definition. I think I like it. (15) is a consequence. I was too quick with (6) in this note. I think it should be ok now.

Thx.